CALIFORNIA’S PRIVATE ATTORNEYS GENERAL ACT OF 2004:

An Assessment of Outcomes and Recommendations for a More Effective Alternative

February 2024

Prepared by: Baker & Welsh, LLC

Original Publication Date: October 2019

1st Reprint (without data updates): November 2020

2nd Reprint (with data updates): January 2021

3rd Reprint (with data updates): September 2021

4th Reprint (with data updates): February 2024

The authors retained sole control over the report writeup and

conclusions.

Prepared by: Baker & Welsh, LLC

Original Publication Date: October 2019

1st Reprint (without data updates): November 2020

2nd Reprint (with data updates): January 2021

3rd Reprint (with data updates): September 2021

4th Reprint (with data updates): February 2024

The authors retained sole control over the report writeup and

conclusions.

This report represents the most comprehensive review of available data regarding Private Attorneys General Act (PAGA) claims filed with the state and with the Labor and Workforce Development Agency (LWDA), the Department of Industrial Relations (DIR) and the Division of Labor Standards Enforcement (DLSE).

PRINCIPAL FINDINGS

Workers receive three times more when their claims are reviewed by the state vs. cases filed with a court.

As shown in Table 1,

- PAGA court case awards average $1,264 per employee vs DLSE wage claim awards averaging $3,613 per employee and DLSE Bureau of Enforcement (BOFE) awards averaging $6,438 per employee.

- Available data from a unit in LWDA that uses DLSE staff to adjudicate a small number of PAGA cases directly are consistent with this underperformance of PAGA court cases—the average payment a worker receives from a PAGA case decided by LWDA-DLSE is three times greater than for a PAGA case filed with a court—$3,956 from a case decided by LWDA-DLSE, versus $1,264 from a court case.

PAGA cases filed with a court take nearly a year longer than claims filed with DLSE or LWDA.

As shown in Table 1,

- Workers filing wage claims directly with DLSE wait 294 days or fewer than 10 months on average for their awards.

- DLSE’s BOFE inspections are concluded with awards to employees in under 10 months.

- Similarly, workers wait on average for 12 months for their PAGA awards from LWDA-DLSE.

- The wait for workers averages 23 months for PAGA court case awards.

Since 2013, employers have been forced to pay nearly $10 billion in PAGA court case awards, but because of the class-action nature of many claims and heavy lawyer commissions, workers receive only a small portion of these awards.

Employers pay far more in litigation fees under PAGA court cases than DLSE cases.

- In addition to paying for a higher award yielding less compensation to employees when a PAGA court case issues an award, employers bear the substantial cost of legal representation, which has not been quantified here. Along with bearing those costs, employers pay an average of $46,000 in additional fees per PAGA case: $28,000 per case for litigation fees, and $18,000 per case is paid to third-party award administrators. Neither of these payments is made when DLSE decides a wage claim or conducts a BOFE inspection.

Letters of intent to file a lawsuit from lawyers can be used to frighten employers into settling before a PAGA lawsuit is filed.

- These settlements are not reviewed by or reported to LWDA or the courts. For this reason, we have no information on what workers receive from these settlements (if anything), what the workers’ lawyers receive, or what the overall settlement amounts are. What’s clear is that with these types of settlements, the state receives nothing.

PAGA cases add the unnecessary burden of having expensive legal representation.

- Attorneys who file PAGA cases with a court are compensated with fees that represent 33 percent or more of the workers’ total recovery, coming to more than $369,882 per case on average. Some cases have awarded attorneys’ fees of 40 percent. There is no need for workers to be paying a lawyer to go to court when they can file a claim without the need for a lawyer and receive a higher award in less time.

Workers are being poorly served by PAGA, and DLSE offers the most effective means for workers to recover wages owed.

- DLSE wage claim adjudication provides the most effective and time-efficient resolution of claims by individuals. Claimants are not required to have an attorney, and most do not.

- DLSE’s BOFE investigations, if adequately resourced, can bring effective enforcement actions against the most prevalent and violative bad actors, which could significantly increase labor law compliance and reduce the need for workers to file wage claims.

The resources exist to handle an increased caseload at DLSE.

- The existing PAGA fund balance could robustly support the staffing increases and administrative changes that would be needed if DLSE were to assume enforcement of labor laws in place of PAGA litigation.

RECOMMENDATION

To improve the claims resolution process and determine just compensation for employees pursuant to wage disputes more equitably and quickly, the state should fund an administrative process that ensures swift and fair recovery for workers, streamlines resolution, removes, or minimizes the need for attorneys to be involved, and is not vulnerable to abuses against either workers or employers.

The resources and experience needed for such a structure did not exist when PAGA was signed into law, but they exist now. The current administrative procedures by which LWDA and DLSE resolve PAGA claims and DLSE’s two units resolve labor law claims using DLSE’s standard methods appear to be substantially more successful for employees than claim resolution by court litigation. However, there is still significant potential to improve the administrative process by reducing unnecessary bureaucracy and reducing the time taken to process claims.

The objective should be an expedited administrative process that delivers a fair result quickly to the workers and employers involved and provides sufficient transparency to track outcomes. This, in turn, will ensure the system is working correctly to serve employees and compliant employers while delivering the remedies needed against noncompliant employers.

Resolution of the claims currently resolved via PAGA should be returned to DLSE. PAGA provides no extra benefit to employees, and it is clear that employees will be better served by fully functional and fully resourced administrative resolution by DLSE.

The languishing PAGA fund, now containing well over $250 million, is more than sufficient to support the startup of DLSE’s resolution of all claims currently being pursued through the PAGA process. Systemic lack of funding that was a principal justification for PAGA no longer exists. DLSE can be supported from that point on through assessment funding, which can easily handle the ongoing cost.

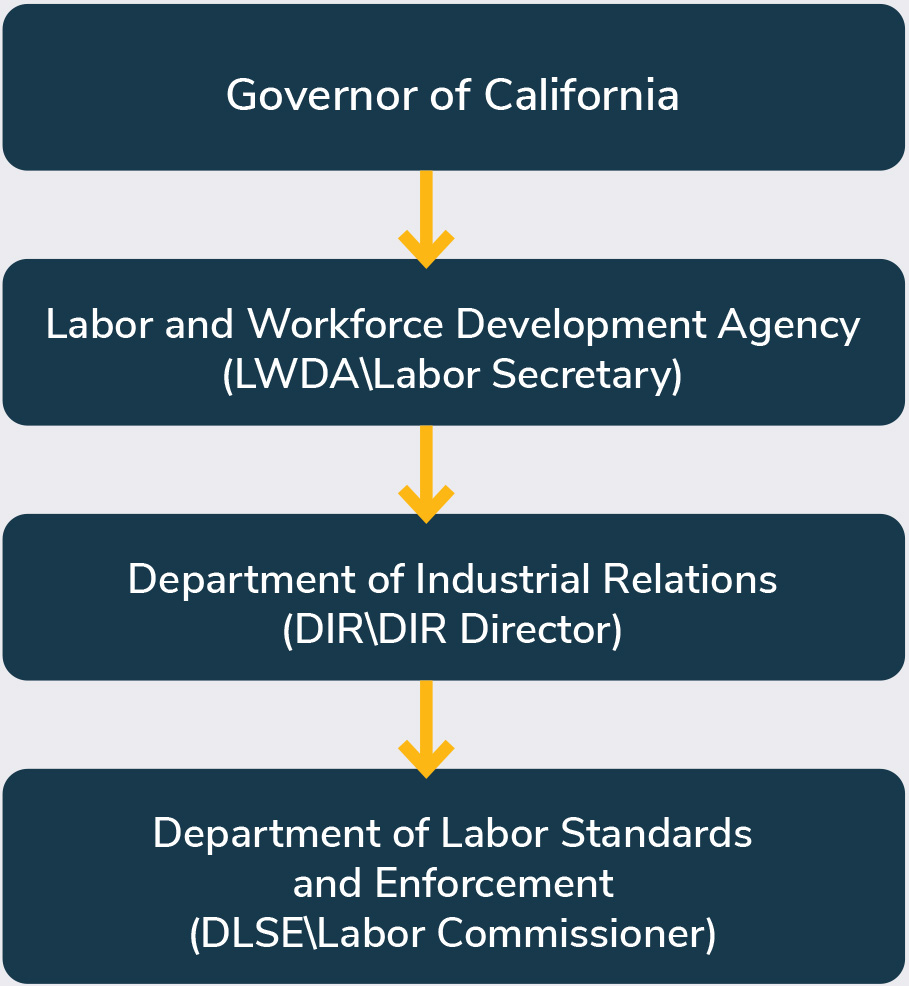

A NOTE ON AGENCY HIERARCHY

LWDA is administered by the Labor Secretary, a member of the Governor’s Cabinet.

The two largest agencies under LWDA’s authority are the Employment Development Department (EDD) and DIR.

DLSE is one of several divisions under the authority of DIR. While LWDA is statutorily charged with the authority to process PAGA cases, it relies directly on DLSE staff to process them, as DLSE is the agency with the most profound expertise needed to perform this function.

INTRODUCTION

This report aims to shine a light on PAGA, contrast this law’s outcomes with those that could reasonably be anticipated from a more effective approach to enforcing and achieving compliance with labor laws, and make recommendations accordingly. This report represents the most comprehensive review of available data regarding PAGA claims filed with the state.

SUMMARY

How we got PAGA.

PAGA took effect in 2004 in California. One of its primary purposes was to supplement public enforcement of the Labor Code with a new, private lawsuit option because DLSE was failing to process claims in a satisfactory manner due to underfunding. DLSE was funded through the General Fund and therefore subject to vulnerabilities of the state’s budget. With ongoing budget shortfalls that continued to result in cuts to DLSE staff and resources, there was increasing pressure to seek an alternative.

That is not the case today, because DLSE is now funded entirely by employers through workers’ compensation assessments.

The enactment of PAGA created an unprecedented opportunity for lawyers to file lawsuits on behalf of an employer’s entire workforce, much like class action lawsuits with numerous plaintiffs, but without the procedural hurdles that limit class actions. PAGA lawsuits enable large awards based on penalties calculated employee by employee, typically resulting in huge fees to attorneys and small recoveries to the individual employees. All that is necessary is at least one employee to volunteer to be a plaintiff, and the resulting PAGA lawsuit can yield an award on behalf of all of the targeted employer’s employees.

This creates a compelling incentive for lawyers to file lawsuits, which has led to what is now the common practice of lawyers recruiting one or more employees to serve as the named plaintiffs to enable these lawsuits.

Under PAGA, employees collect 25 percent of the penalties awarded and the state collects the remaining 75 percent. Added revenue to the state was a critical inducement to acceptance of PAGA by the Legislature and the Governor, but procedural maneuvers perfected over time by plaintiffs’ lawyers have created ways to minimize funds going to the government. As it stands today, funds that have gone to the government have remained largely unused for the purpose they were meant to serve, which was for enforcement of labor laws “...and for education of employers and employees about their rights and responsibilities under this code... .” 1

While LWDA/DLSE can and does decide PAGA claims, the number of claims the agency takes on is small.

PAGA leaves only one minimal hurdle to filing these claims in court: claimants first give notice to LWDA and await that agency’s decision as to whether it will process the claim instead of allowing it to be decided by filing a lawsuit. LWDA’s decision to process the claim must be rendered within a short period of time. If no decision is issued, the claimant may proceed with the lawsuit. The LWDA fails to issue a decision in nearly every case.

Employees who go to court appear to recover substantially less than those whose cases are decided by LWDA/DLSE.

Available data regarding employee recoveries under PAGA actions during FY 13/14 through December 2022 (data collection explained in the next section) indicate that PAGA has not achieved the objective of providing more timely and equitable recoveries to aggrieved employees. The data suggests employees are not receiving better recoveries in the courts under PAGA and if wage claims were administered under a well-conceived and well-resourced administrative process, it is likely that such a process would bring them significantly better and faster results

LWDA does not track most PAGA cases settled out of court, and information on those cases is lacking.

Because of the financially damaging prospect of having to defend against a PAGA lawsuit, employers are vulnerable to being pressured into settling in response to demand letters threatening PAGA litigation. Out-of-court settlements like these are not public, and there is no documentation of the amounts or timeliness of payments to the employees and their lawyers. As a result, there is no means of assuring that employees are receiving what they should when their attorneys receive these settlement proceeds. The state receives no funding if cases are settled out of court

The weaknesses in DLSE funding and staffing that led to PAGA no longer exist.

DLSE is no longer funded by the General Fund. Instead, it is funded by workers’ compensation assessments. Therefore, the funding shortages cited as a justification for PAGA when it was signed into law no longer exist, and there is no impediment to DLSE attaining the funding it needs to process claims efficiently and effectively. The better results for employees LWDA provides, using DLSE staff to process claims, is a testament to the ability of DLSE staff to service employee claims.

What California needs.

These considerations suggest that the California Legislature should review PAGA and consider replacing it with a well-conceived and adequately funded administrative process.

An effective administrative process that will:

- Ensure swift and fair recovery for workers,

- Be streamlined,

- Not depend on the involvement of attorneys, and

- Not be vulnerable to abuses against either workers or employers.

SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY

This analysis is based on the responses received via Public Request Act (PRA) requests for all data on PAGA and DLSE enforcement in possession of LWDA, DIR, and DLSE, the primary government sources of PAGA and DLSE enforcement data. Largely duplicative and procedural documents from individual California courts were not included.

The documents received consist of the contents of files containing information on:

- Data on the enforcement activity of DLSE’s Wage Claim Adjudication (WCA) Unit and Bureau of Field Enforcement (BOFE) Unit.

- PAGA cases administered and decided by LWDA, through its DLSE-staffed “PAGA Unit” —90 cases dating from FY15/16 to December 2022 as of the time LWDA produced the documents.

- PAGA court case files transmitted to LWDA (notices, case awards, or proposed settlements) from 2013 through December 2022.

- Budget Change Proposals (BCPs) to augment LWDA’s oversight of PAGA cases through FY 19/20.

- BCPs to augment DLSE’s WCA and BOFE Units.

- BOFE Legislative Reports.

- Department of Finance (DOF) budget information.

The DLSE enforcement files, LWDA-administered case files, and PAGA court case files transmitted to LWDA, contain information on the length of time from filing of the action to issuance of an award, award amounts, and the workplaces involved in PAGA cases.

Note: Documentation by LWDA of PAGA court case outcomes was largely non-existent for cases filed before July 1, 2016. Information on LWDA documentation of court cases filed after July 1, 2016 is available because of an amendment to PAGA signed into law on June 27, 2016 (SB 836) requiring these documents to be transmitted and retained by LWDA. Although some of this information is incomplete despite the change in the law, the information we have received is the most comprehensive available, consisting of 36,910 PAGA notices2 filed from 09/06/2016 to 12/31/2022, and final or proposed settlements3 totaling 12,537 between FY 13-14 and 12/31/2022.

Using this information, an evaluation was performed to explore and compare three sets of results:

- Enforcement actions conducted directly by DLSE,

- PAGA actions filed with and resolved by LWDA, and

- PAGA actions filed with and resolved by the courts.

Analysis of that information focuses primarily on the following four issues:

- Is the PAGA approach overall producing the benefit that was intended?

- Does the administration of PAGA claims by LWDA as an alternative to court litigation of PAGA claims produce better outcomes than court litigation?

- Would direct enforcement by DLSE of cases now filed in courts under PAGA provide the best remedy for workers?

- Could direct DLSE enforcement be more effective by changing the procedures and personnel employed to process the claims?

DISCUSSION

COMPARISON OF DLSE CASES, LWDA-RESOLVED PAGA CASES, AND COURT FILED PAGA CASES

As can be seen from this table, employees recover the least amount of compensation and wait longer to receive it when their claims are brought to court as a PAGA case. DLSE wage claims and BOFE inspections produce the best results for workers.

MORE DETAIL ON PAGA COURT CASE INFORMATION

According to LWDA’s records, the number of PAGA notices has been relatively constant year over year (Chart 1). Chart 2 shows an approximate 200 percent increase in the number of awards from 2017 to 2022. SB 836, a bill requiring electronic submissions, took effect June 27, 2016, and the low numbers in 2016 reflect how small the amount of information being collected by LWDA was before SB 836 took effect.

As seen in Chart 2, PAGA proposed settlements have been increasing steadily since 2016. Similarly, as shown in Chart 3, the total yearly amounts of settlement awards have been increasing dramatically as well.

Data was obtained from the LWDA, DIR, PAGA Unit through several Public Records Act (PRA) requests for data covering FY 13/14 to January 2021 and February 2021 to December 2022.

The amount of PAGA litigation and the total amounts of yearly awards continue to increase, but the benefits to employees are significantly less than what they would receive if they had filed claims with DLSE instead of filing lawsuits under PAGA in court.

OUTLOOK FOR A RETURN TO ADMINISTRATIVE ENFORCEMENT AS A BETTER APPROACH THAN CONTINUED RELIANCE ON PAGA

As discussed above, the prime justification for the passage of PAGA was the lack of resources for DLSE to process wage and hour claims, resulting in long delays for employees entitled to recovery. The lack of resources was due to DLSE’s dependence on the General Fund, which at the time was significantly stressed. However, funding for almost all of DIR, including DLSE, no longer depends on the General Fund, as several legislative changes over time have resulted in an entirely new source of funding: assessments on workers’ compensation premiums or self-insurer premium equivalent.

These assessments are flexible, they are routinely adjusted to meet the needs of the agency functions they support, and as an agency fully funded by the assessments, DLSE benefits from the ability to have its funding needs fully met by this mechanism.

In addition to the availability of funding via this route, DLSE could and should be able to tap the large funding reserve accumulated from PAGA recoveries. According to a document titled “PAGA Unit Staffing Alignment Budget Change Proposal,” uploaded by DIR to the Department of Finance website in May 2019, as well as State Budget Fund Condition Statements4, the LWDA has accumulated a reserve from PAGA recoveries that should total $356.7 million after the repayment of temporary loans the PAGA Fund has made to the General Fund (see Chart 4). Given the statutory purpose of the PAGA Fund, it would be entirely consistent with PAGA for that money to be used to reboot DLSE in a form that would properly serve workers and compliant employers.

According to Fund Condition Statements, the projected fund balance was estimated to be $249.7 million for FY 23-24 (Chart 5). Reserves shrank in FY 20-21 to $113.7 million due to a $107 million loan from the PAGA fund to the General Fund. Assuming the $107 million loan will be repaid in FY 24-255, the fund balance, without considering new PAGA revenue for that fiscal year, should come to $356.7 million.

DATA COMPARING LWDA-DECIDED CASES TO COURT CASES

Analysis was carried out of the case outcomes regarding dollar amounts and durations for LWDA/DLSE PAGA cases and PAGA court cases (Table 2). Among other notable results, the data reveals that while the average total case award amounts of LWDA/DLSE-decided cases and PAGA court cases appear comparable, the employee award amount is significantly higher when LWDA/DLSE decides the case.

DURATION OF LWDA/DLSE PAGA CASES AND PAGA COURT CASES

Long delays in processing cases due to the Labor Commissioner’s understaffed administrative process was one of the original justifications for PAGA. The following data from LWDA and DLSE reveal case start and award dates for LWDA/DLSE PAGA cases and PAGA court cases. On average, LWDA-retained cases are concluded in 310 fewer days than PAGA court cases (Table 3).

WAGE CLAIM ADJUDICATION AND ENFORCEMENT DETAIL

The Wage Claim Adjudication Unit in DLSE adjudicates wage claims on behalf of workers who file claims for nonpayment of wages, overtime, or vacation pay pursuant to California Labor Code sections 96 and 98. When a wage claim is filed, a DLSE deputy holds an informal conference with the employee filing the claim and the employer to attempt to resolve the dispute. Typically, wage claims are filed by single employees, although claims can be filed by several employees against an employer. If the claim cannot be resolved at the informal conference, an administrative hearing is held to make a final determination.

Basic wage claim data are shown in Tables 4 and 5 below.

Average time for DLSE staff to resolve a wage claim (Table 5) is less than half that of PAGA court cases (Table 3). The Wage Claim Unit was designed (see legislative history) to have the expertise and knowledge and procedures to resolve these types of cases more quickly than litigation through the courts (PAGA and class action proceedings). The data referenced herein supports the finding that workers receive more timely resolution of claims when they are filed with the DLSE. Average awards to workers are greater, and awarded on average more than a year sooner, than claims processed through the courts via PAGA (Table 2).

BUREAU OF FIELD ENFORCEMENT (BOFE) DETAIL

The other enforcement arm of DLSE is BOFE, which is statutorily charged with the duty to conduct investigations and take enforcement action to ensure that employees are neither required nor permitted to work under unlawful conditions. These investigations can be triggered by complaints or DLSE acting on preliminary information indicating that an investigation is called for.

BOFE investigations typically support the enforcement of laws requiring minimum wage and overtime pay rates, child labor restrictions, workers’ compensation insurance, and prevailing wage rates applicable to public works jobs. Enforcement actions can consist of collecting unpaid wages, confiscating illegally manufactured garments, issuing citations for violations of applicable Labor Code sections, and injunctive relief to prevent further violations of the law.

BOFE focuses on major underground economy industries in California with the most rampant labor law violations, including agriculture, garment, construction, car wash, and restaurants.7

Publicly reported BOFE cases from March 2020 to March 2023, as described in DIR press releases, indicate an average of 689 aggrieved employees per case and an average award per employee of $6,438.

ABOUT THE REPORT AUTHORS

David Lanier

In 2013, David Lanier was appointed by Governor Brown to serve as Secretary of the California Labor and Workforce Development Agency (LWDA). Lanier served until 2019.

Prior to his appointment, Lanier served as Chief Deputy Legislative Affairs secretary to Brown and spent nearly two decades serving in leadership positions in the California Legislature. From 1999-2011, he was a Principal Consultant and Special Advisor at the Assembly Speaker’s Office of Member Services. Lanier served as Chief of Staff for Assemblymember Grace Napolitano from 1997-1998, Senior Consultant for the Joint Legislative Government Oversight Task Force from 1996-1997 and Legislative Director for Assemblymember Carole Migden from 1995-1996.

Lanier currently serves as principal at Lanier Consulting, LLC. He holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of California, Berkeley.

Christine Baker

In 2011, Christine Baker was appointed by Governor Brown to serve as Director of Industrial Relations (DIR). She served until 2019 and was the first woman to lead the Department. Prior to being appointed, she served for two decades as Executive Director of the Department’s Commission on Health and Safety and Workers’ Compensation.

She served on the Fraud Assessment Commission, a part of the California Department of Insurance, having been appointed by Governor Brown in 2019 until 2023. She is currently on the board of directors of the International Workers’ Compensation Foundation and an advisor of the National Academy of Social Insurance research team.

Baker is also a principal at Baker & Welsh, LLC, a firm she co-founded with Len Welsh in 2018. She holds a master’s degree and advanced to Ph.D. candidacy at the School of Education, University of California, Berkeley, before leaving academia to take a position at DIR.

Len Welsh

In 2003, Len Welsh was appointed by Governor Schwarzenegger to serve as Chief of the Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA). Prior to being appointed, Welsh served as Counsel and Special Counsel for the division for over 12 years.

As Chief of Cal/OSHA, he lead the adoption of a number of groundbreaking, first-in-the-nation occupational safety and health standards, including the Aerosol Transmissible Disease Standard. After leaving Cal/OSHA, he served as Acting Chief Counsel in the Department of Industrial Relations (DIR).

He also serves as counsel to a number of labor-management partnerships operated by the Western Steel Council and Ironworkers International.

Welsh is also a principal at Baker & Welsh, LLC, a firm he co-founded with Christine Baker in 2018. He holds a master’s from the University of California, Berkeley, and a juris doctorate from University of California, Hastings College of the Law.

1. “Per Labor Code section 2699(j), civil penalties recovered under paragraph (1) of subdivision (f) shall be distributed to the Labor and Work- force Development Agency for enforcement of labor laws, including the administration of this part, and for education of employers and employees about their rights and responsibilities under this code, to be continuously appropriated to supplement and not supplant the funding to the agency for those purposes.” 2. Per Labor Code section 2699.3(a)(1)(A), the aggrieved employee or representative shall give written notice by online filing with the Labor and Workforce Development Agency and by certified mail to the employer of the specific provisions of [labor] code alleged to have been violated, including the facts and theories to support the alleged violation. 3. In most cases, only the proposed settlement amounts are recorded by LWDA, and the final amount is not known. However, the proposed settlement amounts would be expected to closely match the final award amounts. 4. State Budget Fund Condition Statements, Fiscal Years 2019-2020 through 2023-2024. 5. Department of Finance Summary of Budgetary Loans, January 2023. 6. This number represents the amount as of the end of 2022. Recently received data from LWDA indicate that this amount has increased by $1,404,995,248 during the first half of 2023, bringing the total to $9,954,169. 7. 2019-2020 The Bureau of Field Enforcement Fiscal Year Report California Labor Commissioner’s Office Department of Industrial Relations.